On Note-taking as You Read

Suggestions to take, leave, or--even better--bend to make your own

Hello dear Reader & Writer-ites!

I can’t tell you how glad I am to be writing this post today; to be back to the rhythms of everyday. I know I mentioned in an earlier post that my essay writing would be less in January. I didn’t expect it to be as “less” as it has been. My husband and I had to make an unexpecteed trip to our hometown in IL over the past week. We are thankful we were able to go. We are glad to be home.

And, now it is February of 2025 (!), and I am writing to almost triple the readership we had only six weeks ago. Hooray! And welcome! I’m beyond thrilled you’re here.

Recently, my sister texted asking me for tips on note-taking when reading older (read: more difficult, complex, pick-your-word) works of literature. She explained that while she loves reading old books, she sometimes becomes lost in the high style of the language, maze of characters, elaborate descriptions of place, etc.

I get it. Even the most accessible of 19th century British novels are vastly different in structure and style than anything from the mid-20th century forward.

We love old books here on R&W. And, we happen to be reading quite a few of them in 2025: War and Peace, The Odyssey, Moll Flanders, and Middlemarch. My sister’s question got me thinking: maybe there are those among the R&W reader- and listenership who would find note-taking tips helpful as well.

What follows is a (much) expanded version of what I offered my sister. Outside of a few technical notation suggestions, what you will find are tips for things to look for as you are reading. They are only suggestions! Use the ones that make sense to you, or are areas of weakness when reading difficult works. Leave the rest. Hopefully, there are enough ideas here for all the unique ways you are wanting to engage more deeply with the stories you read.

Also, there is a plethora of great note-taking advice out there. Two that come to mind:

Noted, by Julia Hess (entire Substack devoted to note-taking)

On the Marking of Books, 2022 article by Jacob Allee on his Substack, Study the Great Books

If you know of others, please share in the comments section below.

On to my own suggestions.

First and foremost: Have fun! Treat deep reading (and subsequent note-taking) like a personal treasure hunt. You are looking for those things in the story that are valuable to YOU. The best and easiest way to start is by underlining those places that catch your attention: beautiful language, a strange turn of phrase, a funny bit of dialogue, or description of a character. If it makes you pause, give it some love with a notation.

How do I notate? you ask. There is no one, correct way; or if there is, I don’t know it, or follow it. Some people use different color pens for noting various features (characters, plot, theme, virtues, etc.) Some use symbols to represent those same things. You should do what makes most sense to you; what you will be able to maintain. Here are the ways I notate:

I mark my books with pencil (Pentel Click 0.7 for my fellow writing tool nerds). I don’t love pen ink all over my books. The downside of pencils is they can smudge. The upside is I can erase—we all need to erase sometimes. I haven’t found an erasable pen I love, so I take the occasional smudge with the good.

I primarily underline what I notice. I don’t use symbols or different kinds of marking for different things. I’ve begun circling characters’ names when they are first introduced. Sometimes I double underline or put boxes around words or ideas I notice repeating themselves—like all the ways Anthony Doerr mentions light, or trees, or books and reading, in Cloud Cuckoo Land.

Anything I underline, circle, or box in, I also write something about in the margin, basically a word or two—or sentence, or question—for why I underlined it. This makes it easier for me to find later.

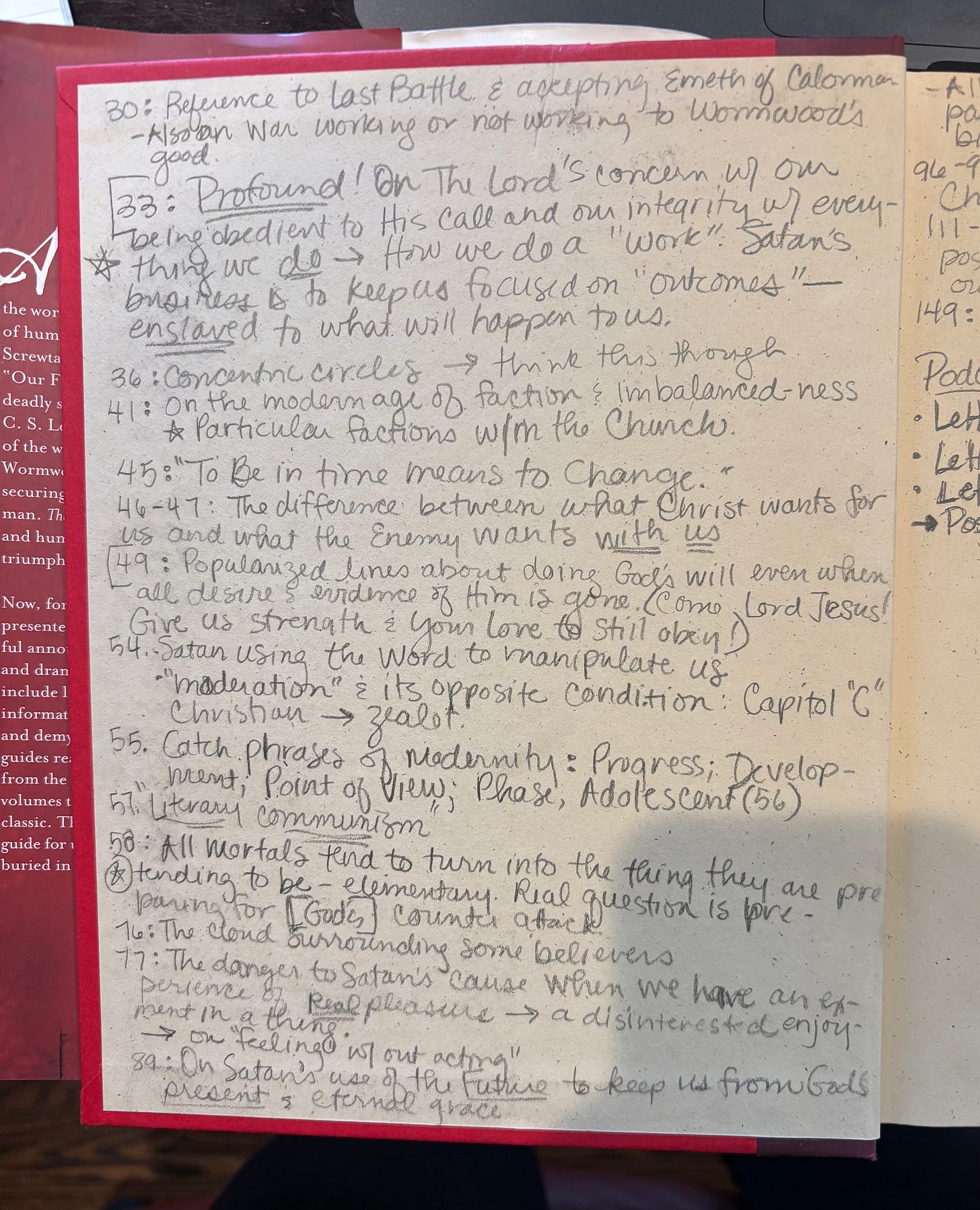

Also—this is a big one for me—anything I make note of within the text, I also notate inside the front and/or back cover of the book, beginning with the page number and then brief description of what I marked. This becomes an index of sorts: when I want to go back and find a description, character, motive or big idea, I can go to my inside book cover “index” and almost always find what I’m looking for. Here’s a photo of my inside cover of The Screwtape Letters:

Rhea’s idea: Post-it note for remembering quotes. Rhea started doing this neat thing where she writes a favorite line or quote from a book on a post-it note. She then sticks the post-it note on the page inside the book where she found the quote. Later, she will move the post-it note to her reading journal and copy the quote into a special notebook reserved for keeping lines she wants to remember. Most people call this a commonplace notebook. I call mine a junk journal, which isn’t the proper term for it, since I didn’t make my journal from recycled materials (or at all). But I do keep scraps of other momentos in the same journal. Also, it was through the idea of junk journaling that I first came across this creative way of keeping quotes, lines, small treasures, etc. So… say what you will. Mine is a junk journal.

Make note of what the novel first gives you. Is it a description of place? (“At sixty miles per hour, you could pass our farm in a minute…” A Thousand Acres, by Jane Smiley) Is it a character? (“Sir Walter Elliot, of Kellynch-hall, in Somersetshire, was a man who, for his own amusement…” Persuasion, by Jane Austen). Is it dialogue? (“Eh bien, mon prince, Gênes et Lucques ne sont plus que des apanages…” War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy) Is it a big idea? (“Happy families are all alike…” Anna Karenina, by Leo Tolstoy) Oftentimes (not always), an author’s opening lines act as a kind of thesis statement, giving us insight into what the story is going to be about, and how much its opening focus is going to factor into the story: whether its a story’s place, or personalities of characters, or the drama of relationships, or overarching big ideas. Notate what you notice about the opening lines—or pages—of a novel.

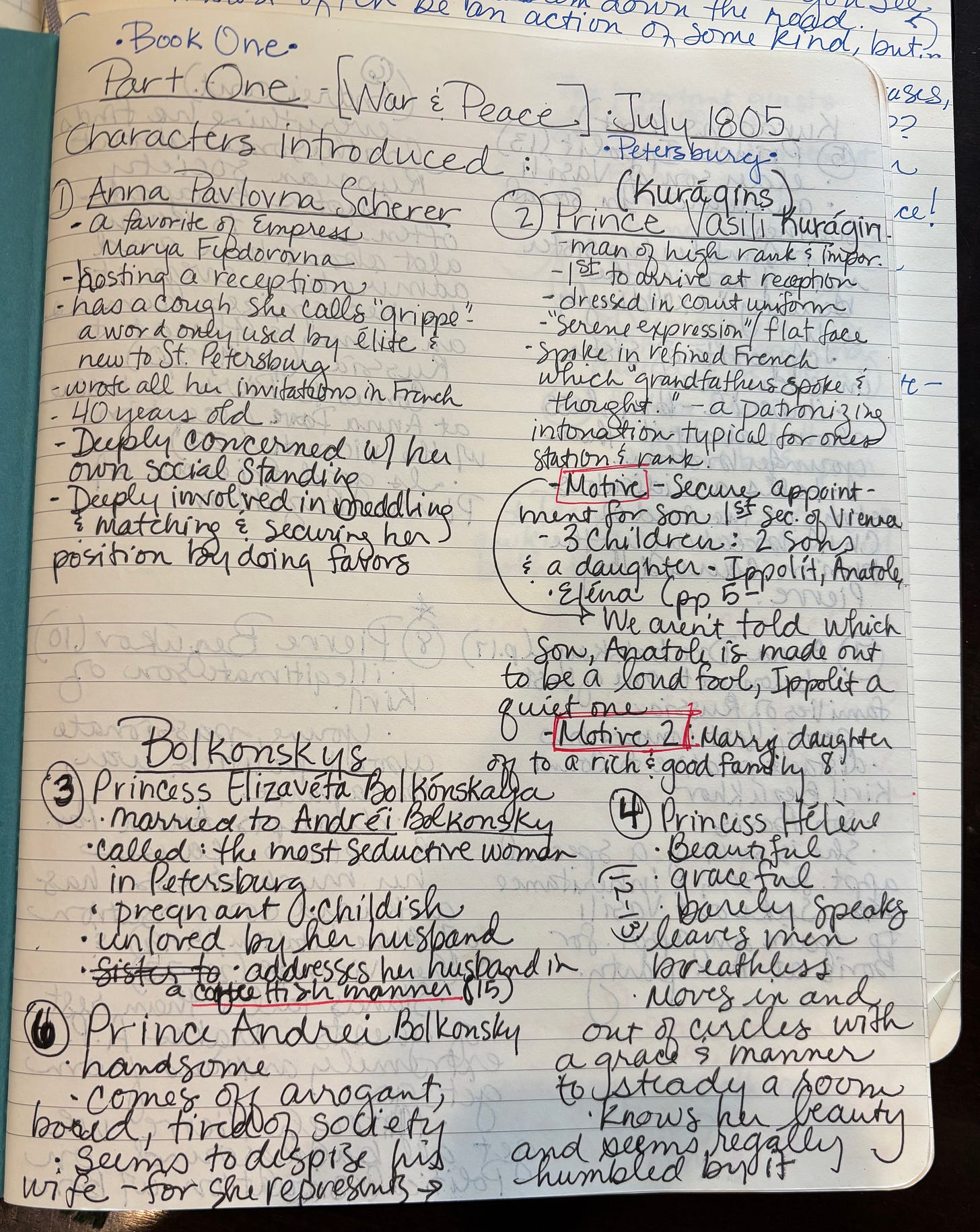

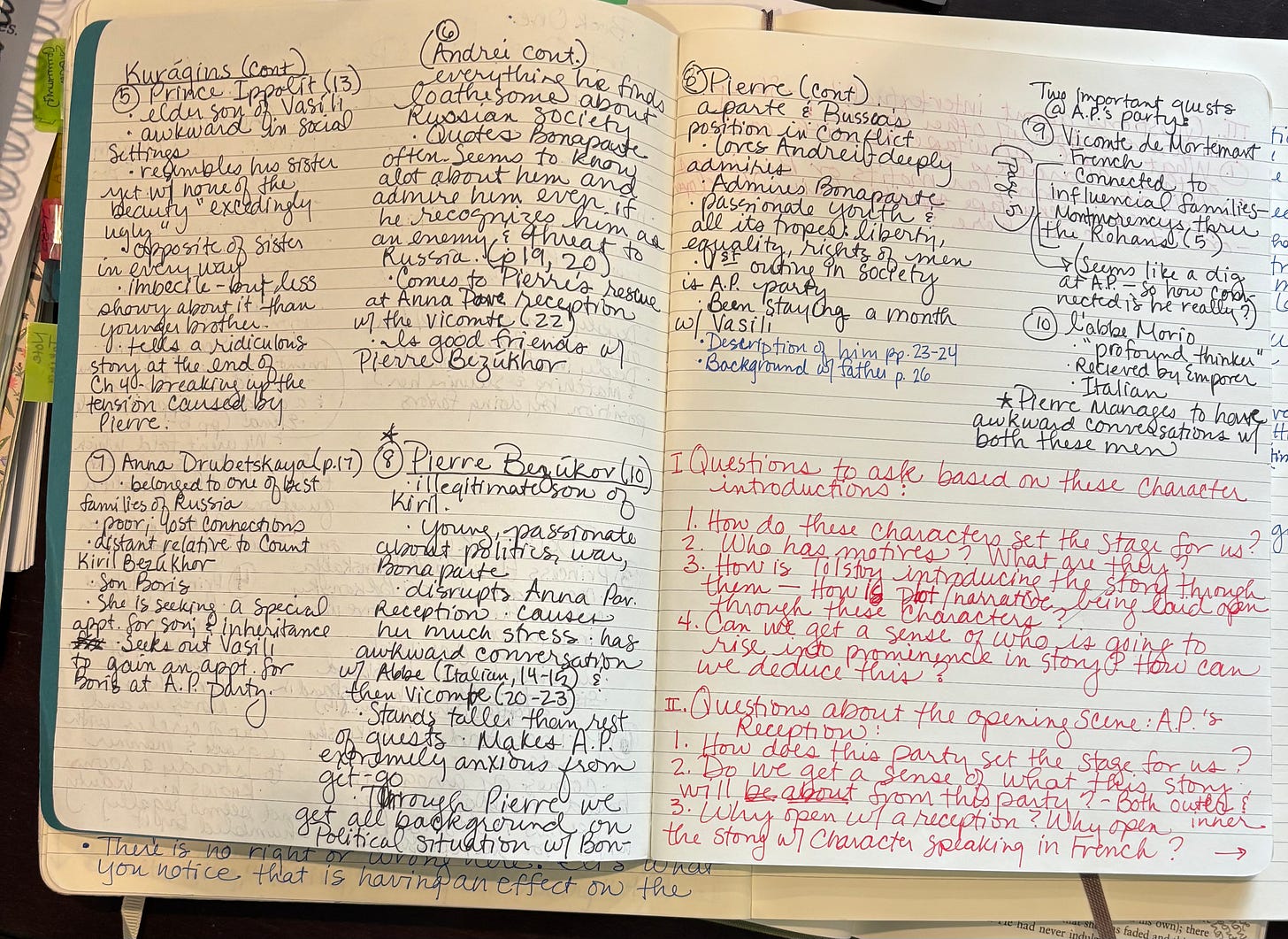

Lean into characters. Literary and classic literature is character-driven (as opposed to plot driven). In the case of classic literature, there are often a LOT of characters (War and Peace, anyone?). Look for all the ways the narrator gives you insights into a character’s personality—or how others perceive a character. When you learn something new about a character, mark it. When there are lots of characters to keep track of, consider making a character tree like Rhea did with the characters from Crossing the Mangrove, or a list-like chart like I’m doing with War & Peace:

You can see that each of our charts reflect our distinct purposes. Rhea was trying to keep track of characters and connect relationships. I was interested in tracking characters’ personalities and motives, in addition to their titles and family connections.

Study narrative strategy. What is this? At its foundation, it is the point of view from which the story is being told. Here are the most common:

1st person: “I” narrator

3rd person “he/she” narrator

3rd person close: “he/she” narrator; only getting one character’s p.o.v., only can be in his/her head, see through his/her eyes.

3rd free indirect: narrator will enter various characters’ minds, one at at time, then generally settle into one or two specific characters and tell the story exclusively through their eyes.

3rd omniscient: narrator has access to all the characters’ minds and freely moves between perspectives throughout the story.

Narrative strategy is more than p.o.v., however. In his craft book, The Art of Perspective, Christopher Castellani calls narrative strategy, “the set of organizing principles that (in)form how the author is telling the story. If perspective is a way of seeing, and narration is a perspective in action, then a narrative stratgey is the how and why of that seeing.” (16)

Questions you can ask when considering narrative strategy: Who is telling this story? Is it the main character? Or someone distinct from him/her? Is it only the main character’s p.o.v. I’m getting? Or others’ perspectives, too? How is the narrator telling the story? Is the story happening in the present? Or being told as past events? Are the events recent past (essentially present, but using past-tense verbs)? Or a long time past? Is there an “emotional experience” that seems to occupy the narrator? What details is the narrator continually leaning into? What effect does this particular narrative style have on the overall telling of the story?

Those are just examples. Springboard your own questions from these.

Mark those moments that appear to affect the story’s trajectory. This is often going to be an action. But it doesn’t have to be. It could be a personality trait in a character you suspect is going to be a problem down the road (think of Eustace in The Voyage of The Dawn Treader). There is no right or wrong here. It’s what you notice.

Consider writing a mini-summary at the end of each chapter. Keep this simple! Use bullet points. Include any of the following:

What happened?

Who was involved?

What new thing did you learn about: characters, relationships, motives, setting, story trajetory, etc.

What was your favorite scene, line, idea, etc.

What new questions do you have?

Any clues to what this story is ultimately about??

Look for possible themes developing as you go. Pay attention to repetitions of words, phrases, ideas, images, character quirks, etc. These often become clues to overarching themes, or big ideas in the story. Remember, a theme isn’t a moral or lesson the author is trying to shove down your throat. It’s a big idea she is exploring and wondering about, even as she is telling a specific story about a specific people in a specific place and time.

Remember #1: Have Fun!

Do you have a favorite note-taking strategy? Please share in the comments below. I’m always up for new note-taking tricks.

As always, thank you for being a part of this R&W growing community!

Until next time…

Read wide, read well, and live always in witness to the Great Story.

Much Love,

Shari

I love this post! Note taking is my love language. Through the act of note-taking, I develop a deeper understanding of the text, myself, and the world around me.

For someone who’s never taken notes while reading, it may feel like work in the beginning however once you get the hang of it, it becomes a reward! One that you can look back on often.

I write in my books and in a journal. This may not be for everyone, but I love doing both. I recently started using Shari’s index method, and I love, love, love it!

For note taking tips, I like Haley Larsen’s Closely Reading. She has an 8-part series on the subject.