Hello everyone! Happy Saturday!

I’ve been thinking a lot about ekphrastic writing since my post last week. I think it’s because I love ekphrastic writing—its beauty, its mystery, its way of pulling me into the life of grace.

And yet, for as much as I love it, I confess I don’t always (or often) slow down the necessary amount of time to participate in it well; to allow those beautiful ekphrastic words have their beautiful sacramental way with me. It’s great to wax poetic about ekphrastic writing’s ability to move us beyond the page and into participating with eternal matters. But it’s all a bunch of airy-fairy nothing if we don’t understand what this looks like.

How do we participate with ekphrastic writing?

Why engage with it at all?

These are the questions I want to adress today.

Why engage with ekphrastic writing?

(If you don’t need convincing of this, by all means, skip to the “Engaging…” section)

Last week, I suggested that ekphrastic writing is, at its heart, the mathmatical equivelent of multiplication, or, the spiritual equivelent of a liturgy1. In other words, the combination of a piece of ekphrastic writing’s parts produces an effect far greater than the sum of its parts.

And what is this “far greater than” that ekphrastic writing produces?

An open door to eternal matters. The torn veil, miracled sight, wheat and water turned to bread and wine. Bread and wine together with body and blood. Sacrament-- tangible means of God's great grace

I don’t know how else to say it.

I also don’t think you have to share or participate in my Christian faith tradition to appreciate this “sacramental” aspect of ekphrastic writing.

When you take the time to study and participate with ekphrastic writing, there is a deep and necessary beauty you cultivate in your life—and in the lives of those around you—simply by recognizing the details in a vivid piece of writing, and contemplating the ways that writing is revealing life to you in ways you’ve not considered before.

It is never a waste of time or effort to study the fine tunings of a fine work (whether written or otherwise) in such a way that ultimately leads you to the question:

How then should I live today?2

Isn’t this ultimately what we’re all aiming at? Isn’t this what we’re longing to discover? Begging for guidance in? How to live well today, and tomorrow, and tomorrow after that?

What I am contending here is that we can actually get at the answer to that question—or at least closer to a grasping of it—in this very “back door” kind of way: by immersing ourselves in those good, true, and beautiful things we meet along the way. In doing so, we can’t help but be changed to “see” beyond the page; to recognize those greater things of life and our relationship to them.

Engaging with ekphrastic writing in a “greater than” way

I once heard a wise art teacher say that for any work of art you want to have a meaningful engagement with (the equivelent of the close, slow or deep reading we do here on R&W), you need to spend at least 90% of your time “noticing,” or examining the piece for all its details, and only 10% or less of your time analyzing, interpreting, and judging the piece.

Withholding judgement until the end, and then only giving it a tiny fraction of time is hard! It’s also not how we do things. Even when we know better. And, let’s be real, oftentimes, we think we are only “noticing” a detail about a thing (or person), but our “noticing” is full of judgement: “Did you see that dress she’s wearing?” Ehem. Need I say more?

But here’s the thing: we do have gut reactions to things. And those gut reactions are demanding little beasts. They insist on being explained. I think this is why we so often go straight to interpretation and judgement. We have this felt need to satisfy the reaction, to make sense of emotional chaos inside us.

With this in mind, I don’t suggest you completely ignore your “gut reactions.” Only set them aside, where you can’t see them, and focus on the noticing. You’ll notice that of my 10 suggestions, nine of them are “noticing.” Only #10 is for analyzing, interpreting, and judging.

Also, what follows here are only my suggestions, mostly written as a series of questions to ask yourself. Just like my note-taking suggestions for deep reading, take what works for you. Leave the rest.

Maybe this goes without saying, but I suggest you write down all your noticing. Either in the margins of the ekphrastic text you are examining, or in a journal… or both. I vote for both.

Here we go…

Participating with the ekphrastic in a sacramental way:

Begin with your five senses: taste, touch, smell, sight, sound.

As you are reading the piece, what do you see? What do you hear? What do you feel (physically)? What sensory words do you notice connected with these sensations? Colors? Smells? Physical touch? Taste or sound?

Move to the sixth sense: proprioception.

Are there places where the point-of-view character is describing him-or herself in space? That is, a kinesthetic awareness to the environment around him (or her)? Where is the character in relation to the thing being described? If you are struggling to answer this, put yourself in the p.o.v. position. Where are you in relation to what is being described? What is your kinesthetic relationship to it?

Notice metaphors, similes (like or as), and other images or descriptive words.

What metaphors are being used to describe the subject matter? What comparisons and/or contrasts are being made? What other images are being conjured?

Notice verbs and verb tense.

What is the verb tense of the description? Is it happening in the present or past? What are the action words of the piece?

Notice alliterations, rhythms, and movement.

Do you see any repetition of sounds? Are they ‘hard’ (like: k, t, p) or ‘soft’ (like: v, m, -sh, -th) Is there a rhythm to the language? Is it lyric? Choppy? Does the scene described seem to move in slow motion? Or are you being rushed through it? Or is there some other kind of movement you are experiencing?

Consider p.o.v.

Whose p.o.v. are you getting? How near or far is the p.o.v. away from the thing being described? Does the “camera lens” zoom in and out? Or do you remain the same distance from the object throughout the description? How close do you get? Inside the p.o.v.’s character’s head? Only at their elbow? Mark where you feel closer or further away from the object being described.

Notice what is “off the page”.

What is mentioned that not in the frame of the description? What is the writer remembering? Referencing? What is she pointing at that isn’t in direct view of what is being described?

Recognize the emotions and big idea of the piece.

What emotions is the author conjuring, either directly, or indirectly, through the description? Where and how do you see these emotions being expressed? What big idea or theme does the writer seem to be expressing through the piece? Or, (as I often say on the R&W podcast) what is the ekphrastic writing’s aboutness, beyond what it is about?

Notice your own emotions, memories, and reactions.

What moves you about this piece of vivid writing? What confuses you? Where are you drawn into it? Where are you repulsed? What does it make you think of? What memories does it conjure in you? What emotion words would you use to describe your reaction to the piece? Where does the writing come alive for you? Where does it have momentum? Force? Where does it ‘pack a punch’ for you personally?

How then should you live today?

Now. Now you can analyze, interpret, and judge all your noticing, and consider how you are being called to respond. How is the work’s theme intersecting your life? What deeper way is it inviting you to participate in your life and relationships?

If you are a person of faith, you are praying and asking the Lord what He is asking you to see. What is He nudging you toward? Put your hands to? Confess? Let go of? Give thanks for?

Ekphrastic writing for your practicing pleasure:

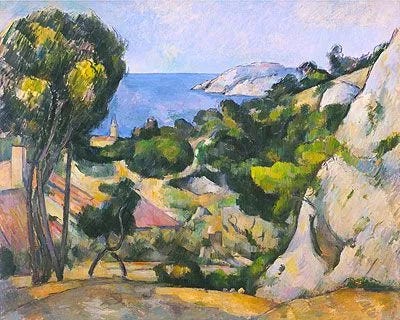

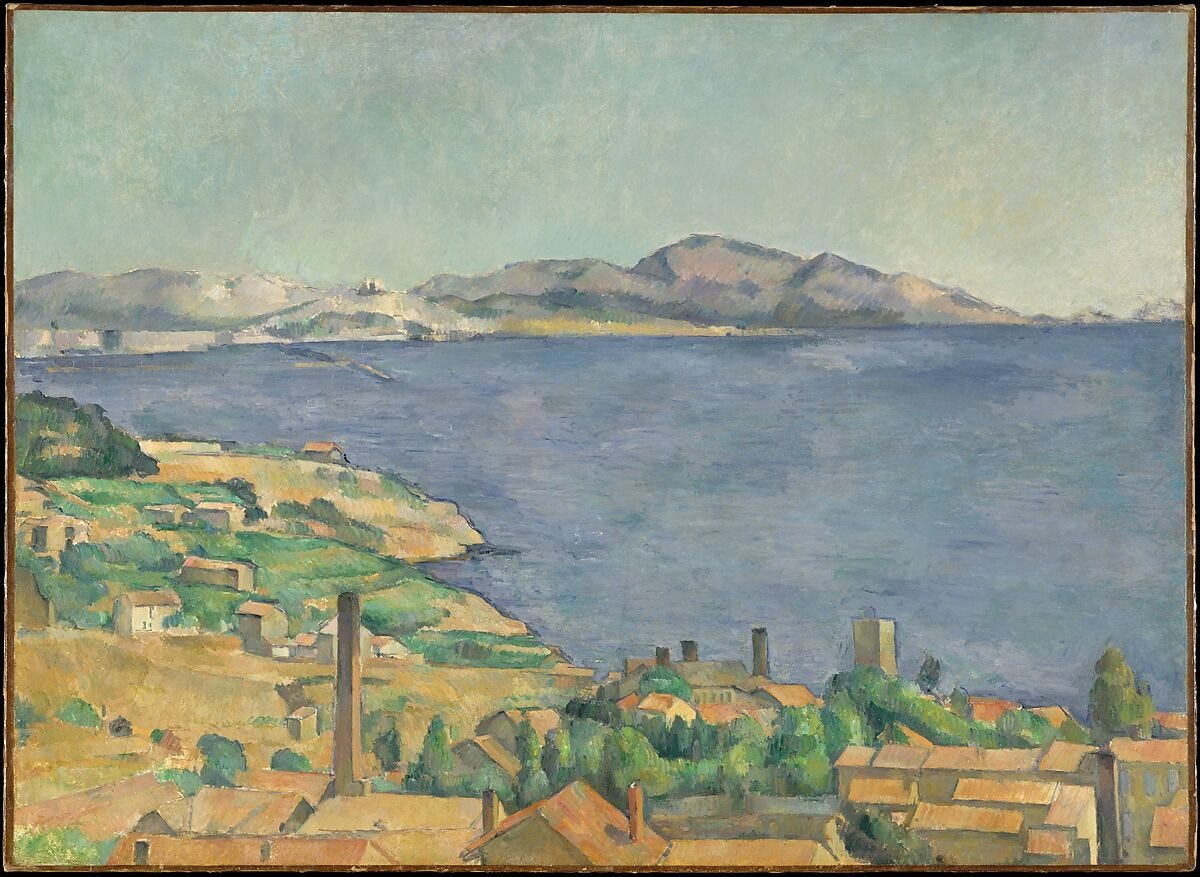

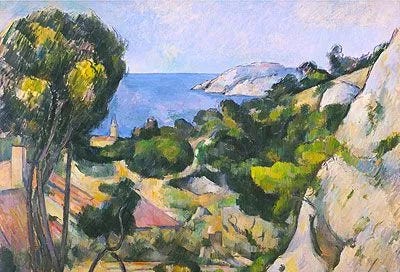

Below are two ekphrastic pieces for you to play around with. The first is a poem by Allen Ginsberg based on the artwork, L’Esaque, painted by Paul Cezanne. The second is a scene from War and Peace, after Prince Andrei is wounded at Austerlitz.

Please share your experience of engaging with either (or both) pieces in the comments section below.

Cezanne's Ports

By: Allen Ginsberg

In the foreground we see time and life

swept in a race

toward the left hand side of the picture

where shore meets shore.

But that meeting place

isn't represented;

it doesn't occur on the canvas.

For the other side of the bay

is Heaven and Eternity,

with a bleak white haze over its mountains.

And the immense water of L'Estaque is a go-between

for minute rowboatsFrom War and Peace:3

‘What is this? Am I falling? My legs are giving way,’ thought he, and fell onhis back. He opened his eyes, hoping to see how the struggle of the Frenchmen with the gunners ended, whether the red-haried gunner had been killed or not, and whether the cannon had been captured or saved. But he saw nothing. Above him there was now nothing but the sky—the lofty sky, not clear yet still immeasurebly lofty, with grey clouds gliding slowly across it. ‘How quiet, peaceful, and solemn, not at all as I ran,’ thought Prince Andrei ‘—not as we ran, shouting and fighting, not at all as the gunner and the frenchman with frightened and angry faces struggled for the mop: how differently do those cluds glide across that lofty infinate sky! How was it I did not see that lofty sky before? and how happy I am to have found it at last! Yes! All is vanity, all falsehood, except that infinite sky. There is nothing, nothing, but that But even it does not exist, there is nothing but quiet and peace. Thank God!…

Remember, only go through those ‘noticing’ steps that are helpful to you. Keep your ratio of noticing to judging at 90/10. And have fun! :)

“liturgy” comes from the Greek word, leitourgia (laos - people and ergon - work). As Alexander Schmemann explains it in his book, For the Life of the World, a leitourgia meant an action by which a group of people become something corporately which they had not been as a mere collection of individuals—a whole greater than the sum of its parts. (p. 34)

This question comes from the theologian, Francis A. Schaeffer, and is the title to one of his most well-revered books.

From the Oxford World’s Classics, Louise and Aylmer Maude translation, p. 299

Oh that we as a society would approach so much more of our decision making in this 90/10 practice!