Hey there, everyone. Happy Thursday! And thanks hanging here with me on the R&W Substack. :)

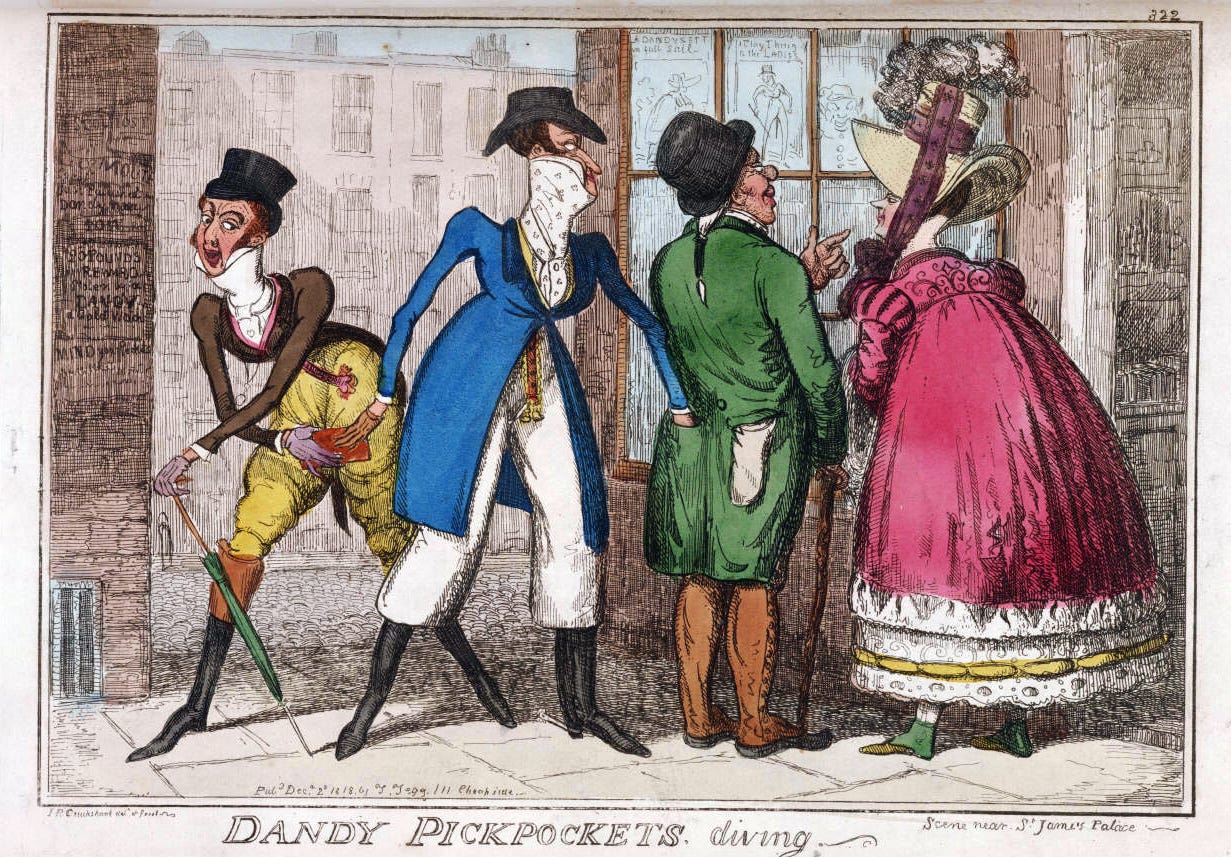

I hope you’ve been reading Moll Flanders by Daniel Defoe alongside Rhea and me. We are over half way through the novel. This fourth section of the story has felt a little sloggy to me. Maybe I’m tired of watching Moll’s train wreck of a life. Maybe I’m losing compassion as she shamelessly throws herself into a life of thievery like its essential to her being, acting as though it’s as essential as the air she breathes. Rhea made an apt comparison in the last podcast episode: Moll has become an addict. Her obsession with obtaining this image as a Gentlewoman has ultimately led her down the primrose path of self-destruction worse than all her other mishaps combine.

But, while I might find this section of the story reading a bit like a sailing vessel stuck in the doldrums, I have recognized something of (I think) supreme importance that Defoe is doing: He’s giving Moll what’s she’s wanted from the beginning: the title of Gentlewoman.

If you read last week’s post, you know Moll has a deep seated desire to be a Gentlewoman. You also know this is a position she can literally never attain in the time and place in which she lives (18th century England’s social class system).

Nevertheless, Moll pursues and pursues and pursues. For the first half of her life she seeks the Gentlewoman status through marriage. Marriage after failed marriage, leaving a string of motherless children in her wake (eight? nine? Rhea and I have lost count). After her last husband dies, out of desperation and fear of poverty, Moll “falls” into thievery, just as she “fell” into giving herself away sexually, all for the sake of landing that coveted Gentlewoman status.

The irony is, more than any other part of her story, Moll, the infamous thief, is graced with the title Gentlewoman by the very unsuspecting society she walks amongst and regularly thieves. Everywhere she goes she is called Gentlewoman. Moll uses this to her advantage, and even when she isn’t the explicit “thief,” she manipulates her image as a Gentlewoman to con others into paying her reparations when wrongly accused, essentially thieving in a different way. Moll raises her chin, puts up an affront over the audacity of being accused of such despicable behavior, and sends men falling over themselves apologizing to “the Gentlewoman.”

This is Moll describing one such incident (this is one time when she wasn’t the actual thief, but was dressed as a widow with every intention to thieve):

By this time some of his Neighbours having come in, and, upon inquiry, seeing how things went, had endeavour’d to bring the hot-brain’d Mercer to his Senses; and he began to be convinc’d that he was in the wrong; and so at length we went all very quietly before the Justice, with a Mob of about 500 People at our Heels; and all the way I went I could hear the People ask what was the matter? and others reply and say, a Mercer had stop’d a Gentlewoman instead of a Thief, and had afterwards taken the Thief, and now the Gentlewoman had taken the Mercer, and was carrying him before the Justice; this pleas’d the people strangely, and made the Crowd encrease, and they cry’d out as they went, which is the Rogue? which is the Mercer? and especially the Women; then when they saw him they cryed out, that’s he, that’s he; and every now and then came a good dab of Dirt at him…

(pp. 317-318, Moll Flanders, Penguin Classics ed.)

What’s Defoe doing here? Why now, in this part of Moll’s story, is he putting into the mouths of the society around Moll the title of Gentlewoman when describing her?

Asked another way, since this is written as an autobiography by Moll, herself: Why is Defoe having Moll tell us over and over again that she was known as a Gentlewoman everywhere she went. “The Gentlewoman this…” and “the Gentlewoman that….” In this thieving part of her tale, Gentlewoman is how Moll Flanders is named and known by others in the society around her.

Moll may be the one telling us her own story, but behind her pen is the author writing Moll and her story into existence. This word, Gentlewoman, popping up when Moll is at her lowest and least like a Gentlewoman is no accident.

I can’t help thinking of that scene in Forrest Gump when Forrest finds Jenny performing at a topless bar under the pseudonym ‘Bobbie Dylan’ with nothing but her guitar on, singing Bob Dylan’s Blowin’ in the Wind. He becomes all misty-eyed as he watches her, mistaking her compromised position for having finally achieved her dream of becoming a folk singer. (I looked forever for the exact movie clip that includes Forrest’s narrative in the scene. I’m sure it exists, but I was wasting time looking.)

Jenny and Moll are play acting to a crowd that is more than willing to join in the ruse as long as it benefits them in the long run. Maybe they’ve even deluded themselves into believing the lie in front of them. It certainly benefits them to do so. This is more obvious in Jenny’s case—an actual audience of drunk, sex-seeking men.

But, isn’t this the case for the society around Moll, too? After all, social standing was just as much about who you knew as it was about how much money you had (the two obviously went together). If Moll looked like a Gentlewoman, then didn’t it behoove the socialites around her to treat her as such? I mean, you never know when “knowing so-and-so” might come in handy.

Again, what is Defoe doing? How is this constant naming of Moll as a Gentlewoman, when she’s never been further from the reality, serving the story he is trying to tell?

It’s no secret that authors are quite deliberate about their characters’ names. It’s one of many devices for character development, and can even hint at the “aboutness” of the story they are trying to tell—those deeper themes, as well as authorial vision.

But besides the names of their characters, there is a whole host of ways authors use naming to help express the story they want to tell.

Examples:

what the characters are called by others

how the characters name themselves

whether or not these names (and titles) change over the course of the story

Also, characters’ official titles or societal labels: jock, band geek, terf—look it up if you’re not sure, gentlewoman… you get the idea

Moll Flanders offers us an excellent case study here. No one (almost no one) gets a name in this story. Not their real name, anyway. Moll never offers us her real name (unless she does at the end—I’m not there yet.). And she never uses anyone else’s real name either. They go by titles, societal labels, or some other descriptive device.

Only one person’s real name is given and used by Moll: her fourth husband, James. Not only do we get to know James’s name, we get to know Moll’s affectionate nickname for him: Jemy. (She’s married to the man for two-ish months.)

Strange, right?

What is Defoe doing??

I don’t know.

I do know that this constant use of “Gentlewoman” is no accident on his part. And, of course, I have thoughts. But that’s exactly what they are, thoughts. No final pronouncements. Not until the very end. Maybe not even then.

For now, I suggest we take note of each small marvel, and, like Jesus’s mother, Mary, ponder them in our hearts.

What other curious things have you noticed while reading Moll Flanders?

Have you read any other stories where names and titles seem to factor significantly in the story’s telling—and ultimate meaning?

Are there other craft choices of Defoe’s you find significant? For example: the autobiographical style? The lack of breaks in the narrative? Moll as an unreliable narrator?

What else??

I’m excited to hear all your thoughts on any of the above.

Until we meet again, Read wide & read well!

If you liked this essay, you’ll probably also enjoy:

I have a theory on the “not knowing” her real name and can’t wait to discuss it on the podcast. And, it’s more than just she wants to avoid trouble…)