Tragic flaw? Maybe Epiphany.

In which I settle my unsettledness over Persuasion's heroine, Anne Elliot, having no flaw.

I confess: I have been obsessed over the idea that Persuasion’s main character, Anne Elliot, doesn’t have a flaw.

From the moment I read Karen Swallow Prior’s chapter on Persuasion (from her book, On Reading Well) and saw C. S. Lewis’s take on it’s main character, Anne Elliot, as being without flaw, I was skeptical. It goes against all my sensibilities as a reader, and especially as a writer. Characters without flaws are hard to relate to, which makes them hard root for. In short, they are uncompelling. I can’t think of one writing craft book I’ve studied, or workshop I’ve attended where it was taught that the best kinds of characters are those with flawless natures. Particularly in the case of literary fiction where it’s the characters and their inner lives which often lead the way.

Case in point: I am currently poking my way through Writing Fiction: A Guide to Narrative Craft, by Janet Burroway. In her chapter on plot and structure, she quotes Aristotle on the “tragic flaw” intrinsic to the character which serves as the catalyst for the story’s “reversal”:

In the Poetics… Aristotle referred to crisis action of a tragedy as a peripeteia, or reversal of the protagonist’s fortunes. Critics and editors agree that a reversal of some sort is necessary to all story structure, comic as well as tragic. Although the protagonist need not lose power, land, or life, he or she must in some significant way be changed or moved by the action. Aristotle specified that this reversal came about because of hamartia, which has for centuries been translated as a “tragic flaw” in the protagonist’s character, usually assumed to be, or defined as, pride. But more recent critics have defined and translated hamartia much more narrowly as a “mistake in identity” with the reversal coming about in a “recognition.”

When comparing Burroway’s text above to the character of Anne Elliot, one can make the argument that Anne is indeed “changed or moved” by the action of the story. Her situation at the end of the story is drastically different than at the beginning.

But this reversal doesn’t come about because of a “tragic flaw” or a “mistake in identity” from inside Anne. Indeed, when she and Wentworth do find their way back to one another, she doubles down on her decision to end their engagement eight years prior saying that though the advice she was given was flawed, she was not wrong to be persuaded by it.

As C. S. Lewis explains in his essay, “A Note on Jane Austen” (the same essay from which Prior quotes), the mistake in identity, or “self-deception” as he calls it, happens around Anne, not within her.

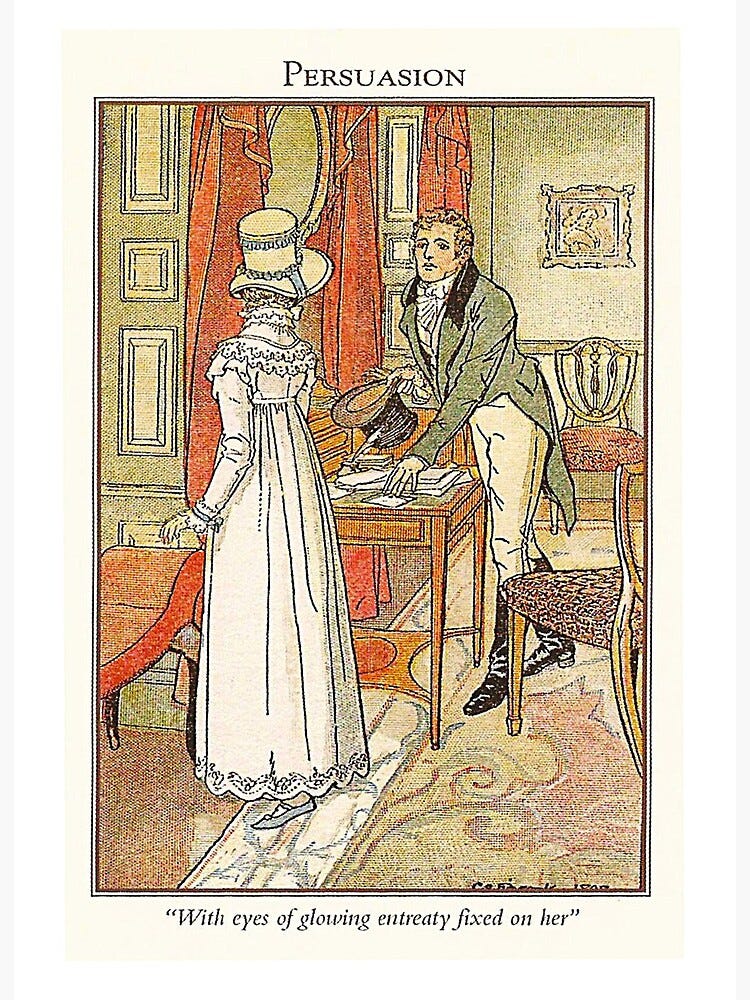

These solitary heroines who make no mistakes have, I believe—or had while she was writing—the author’s complete approbation. This is connected with the unusual pattern of Mansfield Park and Persuasion. The heroines stand almost outside, certainly a little apart from the world which the action of the novel depicts. It is in it, not in them, that self-deception occurs. They see it, but its victims do not. They do not of course stand voluntarily apart, nor do they willingly accept the role of observers and critics. They are shut out and are compelled to observe: for what they observe, they disapprove. (Selected Literary Essays, 181)

Lewis further states that the “deception” of the novel isn’t even the central issue to the story. “Sir Walter is, no doubt, deceived, both in his nephew and in Mrs. Clay,” writes Lewis, “but that is little more than the mechanism of the plot. What we get more of is the pains of the heroine in her role of compelled observer.” (184)

It is the dual work of “compelled observer” and “pain of the heroine,” that I believe draw us in tenderness toward Anne despite her flaw-less nature. From the opening pages of the novel, Austen sets Anne in this “shut out,” discarded position of being “only Anne:”

…but Anne, with an elegance of mind and sweetness of character, which must have placed her high with any people of real understanding, was nobody with either father or sister: her word had no weight; her convenience was always to give way;—she was only Anne.” (Persuasion, Penguin Classic Edition, 7)

Then Austen shows us throughout the novel what she tells us in its opening pages. She writes Anne’s character in such a way that allows us to see and feel Anne’s full humanity: her disheartening insights about her family, her still-yearning love for Wentworth, her deep discomfort in being so relied upon by everyone and yet cherished by no one; all felt in degrees of pain and long-suffering, without the taint of a victim or martyr mentality.

Lewis does concede to two occasions where Anne’s character could be charged with a kind of “priggishness.” One of these is Anne’s “delicacy which must be pained” by watching Henrietta’s mistreatment of Charles Hayter, her cousin to whom she’d been previously attached to until becoming star-struck by Wentworth. The second is Anne’s animated “encouragement” to Captain Benwick, chastising him for nursing his melancholy, and commending him to reading the great English moralists as a medicine against self-indulgent despair.

Of these two, only the second one struck me while reading it as Austen making Anne a bit high-minded and moralistic for admiring. But even here, the thought was fleeting. Soon I was swept back into Anne’s self-consciousness over her own self-consciousness and longing to do well with those situations and relationships given her.

It’s almost as if Austen were writing to embody through Anne the life of the “blesseds” from Jesus’ Sermon:

Blessed are the poor in spirit…. Blessed are those who mourn…. Blessed are the meek…. Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness…. Blessed are the merciful…. Blessed are the pure in heart…. Blessed are the peacemakers…. Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness sake…. (Matthew 5:2-10)

In her continued examination of the “tragic flaw,” or “mistake in identity,” Burroway points out that James Joyce recorded in his notebooks and stories a similar, but slightly altered idea: the moment of epiphany.

As Joyce saw it, epiphany is a crisis action in the mind, a moment when a person, an event, or a thing is seen in a light so new that it is as if it has never been seen before. At this recognition, the mental landscape of the viewer is permanently changed…. it is important to grasp that Joyce chose the word epiphany to represent this moment of reversal, and that the word means “a manifestation of a supernatural being”—specifically, in Christian doctrine, the manifestation of Christ to the gentiles. By extension, then… any mental reversal that takes place in the crisis of a story must be manifested; it must be triggered or shown by an action.

In Joyce’s idea of epiphany, the “tragic flaw,” “mistake in identity,” “self-deception” (take your pick) is of secondary issue, and not the main driver of the story. Rather it is the supremely more important gift of insight that comes to the character from outside him- or herself, that matters. Deception, or the tragic flaw, may still play a mechanistic plot role, as Lewis suggests, but it isn’t necessary that the main character be the one deceived or flawed. Only that she be the one gifted with epiphany.

And epiphany, Anne receives:

In a single letter barely legible and hastily written, Anne is gifted with life-changing insight not so dissimilar from that first Epiphany long ago: the Word enlivened, enfleshed, and exposing His impassioned love to those who, like Anne, were cast off and forgotten by all others; but to Him, were the first and singular focus of His heart’s desire.

I think I am finally settled on this issue of Anne Elliot and her being “without flaw.” :-)

What other encounters have you had with the flaw-less character in literature? Did the author succeed in making him or her compelling still? How so?

Lots to think about; I’d love to hear your thoughts. :)

Read wide, read well, and have wonderful weekend!

With much affection,

Shari