National Poetry Month: Li-Young Lee

"It is finished.... All that's left are love songs to God."

Hello everyone! A somber and glad Holy Saturday to you all. And a pre-Happy Easter - Resurrection Sunday as well!

This week is the last week of our featured poets from An Axe for the Frozen Sea, by Ben Palpant. I saved poet, Li-Young Lee, specifically for this week. It won’t take long for you to understand why.

Palpant’s interview with Lee was long and rich. There was much he said that moved me deeply, and caused long pause, forcing me to slow down and contemplate the force of what he was expressing. It was also this interview that inspired my desire to think and write about how to dwell with a poem.

Needless to say, it has been difficult to narrow down what to share from this interview. We’ll see how I do.

Here are some highlights from Ben Palpant’s interview with Li-Young Lee:

Li-Young Lee

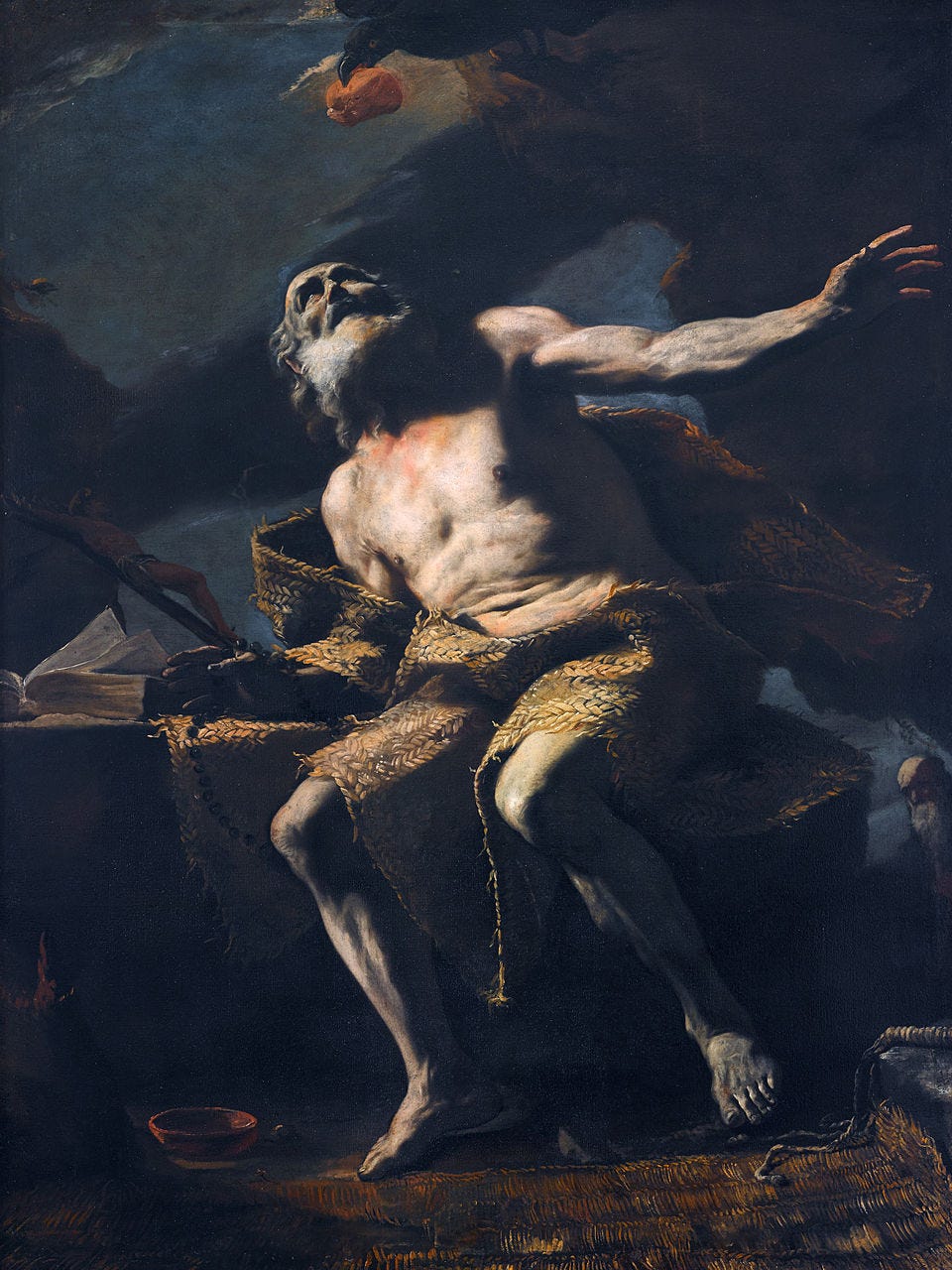

Lee on his recent experience seeing Mattia Preti’s painting “Saint Paul the Hermit” (See painting below this quote):

“I visited the Ontario Museum of Art. There’s a seventeenth-century painting by Mattia Preti called ‘Saint Paul the Hermit.’ It unseated me. The painting might be life-size, I don’t know. In it, there’s so much darkness descending on Paul. So much darkness, Ben. I mean, his robe is falling away from his frail body. At the top, there’s a raven’s head with a morsel of bread in its beak, and Paul is straining toward the bread. He’s straining into that darkness. It’s a darkness full of news.”

“What kind of news?” I ask.

“I don’t know,” he replies. Ultimately, news that’s profound and great, news we’ve forgotten, news we can barely believe. When I saw that painting, I just had to stand beneath it. I thought: ‘It is finished.’ I don’t know why that phrase came to me, but that’s all I could think about. It is finished. I felt this ecstatic thing, this realization that it really is finished. I’m just standing in the wake.”

“…. There’s a darkness that’s pregnant with meaning, you know. It’s a different kind of darkness. It’s not merely dark; it’s something more.”

“You’re reminding me of that passage in Isaiah 50 where God calls his people to trust in the name of the Lord, even when they walk in darkness. He says that if we encircle ourselves with light of our own making—some kind of artificial and temporary reprieve from the darkness—then we will lie down in torment. Such a profound confrontation can happen but we’re afraid of it. We don’t feel strong enough to sit in it, so we distract ourselves.”

“Yes, that’s the darkness I’m talking about. That’s what I’m feeling. It’s absolutely uncomfortable…. A darkness full of yearning, full of good news, but it was so dark. I mean, can you imagine the courage it takes for an artist to enter that darkness with each new project?” (pp. 101-102)

On the tension between stillness and motion:

“I guess what I want to say is that I’m always in the throes of trying to understand the tension between stillness and motion. I sometimes call stillness ‘silence,’ but people don’t understand. They see white space around a poem on the page and call the white space silence, but it’s not silent. The white space is full of noise. The craft, the magic, the Christic imagination that uses words to make a reader feel silence requires a stillness in the poet. Stillness is the mind of being still. All language in a chain—one word linked to the next word—is motion. We study that motion. We notice that it is stressed and unstressed. They really boiled things down for us in a way that can be useful, but it’s not enough. It’s the stillness inside the poet that makes the poem. It’s the stillness that returns the poet to the source.” (pp. 107-108)

On the Christic imagination:

“I keep coming back to this Christic imagination,” he says. “Everything depends on it. Everything exists by virtue of the Christic. Christ was at the very beginning of the world, and everything participates in Christ, whether we know it or not. As a pastor’s son, I grew up hearing this news, but it means much more than I ever realized. If people knew it and could remember it, there would be far less suffering, I think.” (p. 109)

On the life of a poet:

“People imagine that a published poet is surrounded by friends and a thousand demands. Is that true?”

“Actually, it’s really scary and lonely out here. It’s terrifying. And it’s year after year of that kind of work.”

“What do you mean by ‘out here’?”

“I mean that place where the work can get done, that place inside me where I enter the pregnant darkness. Maybe I just don’t like large groups of people. I don’t know what I’m saying.” He pauses again. “I just keep coming back to those three words—it is finished. If it’s true that it is finished, then I’m free to live in those three words. The prayer of my life and my work has that much more meaning: It is finished makes me cry, O my God. O my love. Holy, holy, holy. Those are the attitudes of all great lyric poetry. All great poetry is some variation on those three themes. There are so many ways, so many inflections you can use to praise.” (p. 113)

On writing out of grief and not grievance:

“A few years ago, you said that many American poets come to their work work with complaint, not praise, and so their poetry lacks richness and depth. You said, ‘We should write out of grief, but not grievance. Grief is rich, ecstatic. But grievance is not—it’s a complaint, it’s whining.’ That problem has only worsened over the last few years. At least, it seems so to me. Now we are catechizing our children in the doctrine of complaint. We’re in a vicious cycle of complaint, rage, and self-destruction. It’s the air we’re breathing, so it’s easy to start doing it, too. I wonder if you see any solution. Is there still hope for us?”

“We have forgotten how to praise anything but ourselves and our agendas,” he says. “No wonder there are so many problems in the world. Forget yourself. Stop looking at yourself. Forget all the grievance. The only thing left is love-talk to God.” (pp.117-118)

Poems

Du Dunkelheit, aus der ich stamme

(You darkness, of whom I am born)

By: Rainer Maria Rilke

(from: Rilke’s Book of Hours: Love Poems to God)

You, darkness, of whom I am born–

I love you more that the flame

that limits the world

to the circle it illuminates

and excludes all the rest.

But the dark embraces everything:

shapes and shadows, creatures and me,

people, nations–just as they are.

It lets me imagine

a great presence stirring beside me.

I believe in the night.

Gravity's Law

By: Rainer Maria Rilke

(from: Rilke’s Book of Hours: Love Poems to God)

How surely gravity's law,

strong as an ocean current,

takes hold of the smallest thing

and pulls it toward the heart of the world.

Each thing—

each stone, blossom, child —

is held in place.

Only we, in our arrogance,

push out beyond what we each belong to

for some empty freedom.

If we surrendered

to earth's intelligence

we could rise up rooted, like trees.

Instead we entangle ourselves

in knots of our own making

and struggle, lonely and confused.

So like children, we begin again

to learn from the things,

because they are in God's heart;

they have never left him.

This is what the things can teach us:

to fall,

patiently to trust our heaviness.

Even a bird has to do that

before he can fly.

Arise, Go Down By Li-Young Lee It wasn’t the bright hems of the Lord’s skirts that brushed my face and I opened my eyes to see from a cleft in rock His backside; it’s a wasp perched on my left cheek. I keep my eyes closed and stand perfectly still in the garden till it leaves me alone, not to contemplate how this century ends and the next begins with no one I know having seen God, but to wonder why I get through most days unscathed, though I live in a time when it might be otherwise, and I grow more fatherless each day. For years now I have come to conclusions without my father’s help, discovering on my own what I know, what I don’t know, and seeing how one cancels the other. I've become a scholar of cancellations. Here, I stand among my father’s roses and see that what punctures outnumbers what consoles, the cruel and the tender never make peace, though one climbs, though one descends petal by petal to the hidden ground no one owns. I see that which is taken away by violence or persuasion. The rose announces on earth the kingdom of gravity. A bird cancels it. My eyelids cancel the bird. Anything might cancel my eyes: distance, time, war. My father said, Never take your both eyes off of the world, before he rocked me. All night we waited for the knock that would have signalled, All clear, come now; it would have meant escape; it never came. I didn’t make the world I leave you with, he said, and then, being poor, he left me only this world, in which there is always a family waiting in terror before they’re rended, this world wherein a man might arise, go down, and walk along a path and pause and bow to roses, roses his father raised, and admire them, for one moment unable, thank God, to see in each and every flower the world cancelling itself.

From Blossoms By Li-Young Lee From blossoms comes this brown paper bag of peaches we bought from the boy at the bend in the road where we turned toward signs painted Peaches. From laden boughs, from hands, from sweet fellowship in the bins, comes nectar at the roadside, succulent peaches we devour, dusty skin and all, comes the familiar dust of summer, dust we eat. O, to take what we love inside, to carry within us an orchard, to eat not only the skin, but the shade, not only the sugar, but the days, to hold the fruit in our hands, adore it, then bite into the round jubilance of peach. There are days we live as if death were nowhere in the background; from joy to joy to joy, from wing to wing, from blossom to blossom to impossible blossom, to sweet impossible blossom.