Hello everyone! Happy Friday, and happy October (already—yikes!)

Two weeks ago, I wrote about the story of Esther and how it harmonizes with the Arabian Nights tales which Rhea and I have been reading and discussing on the podcast.

This week, I want to move into part two of that post which considers the question: What is the value of reading the Bible as literature?

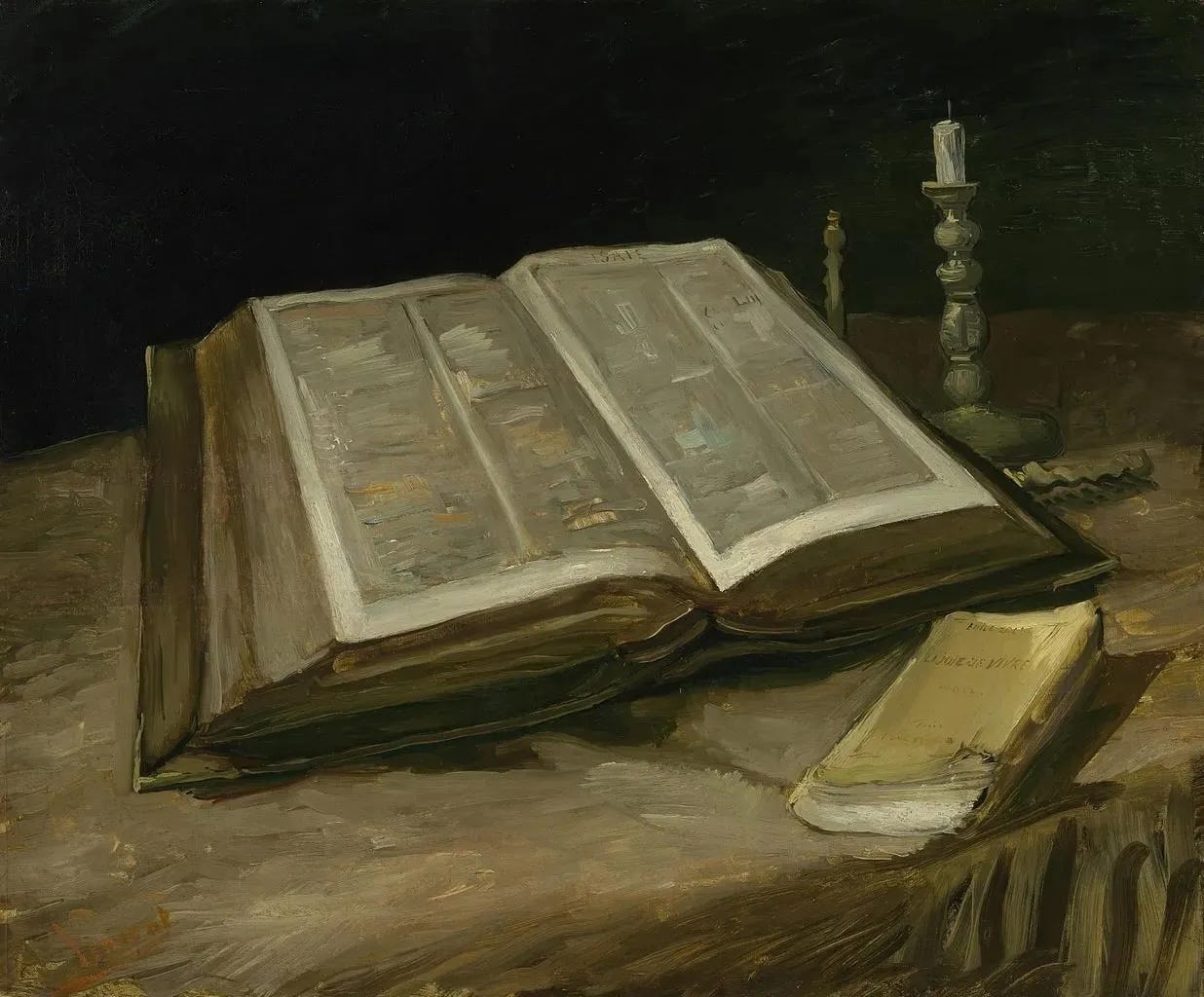

Two weeks ago, I was sitting on a plane, traveling to see my son’s college football team play against Millsaps College in Jackson, MS. Folks were still boarding, so I took the opportunity while still grounded to pull out my Literary Study Bible and read the Esther story, mining for ways Esther rhymed with the tales from The Annotated Arabian Nights. As I was reading a young man claimed the seat next to me, situated himself and then looked over to what I was reading.

Without hesitation or reserve, he asked, “May I ask what you are reading?”

“Sure,” I said. “I’m reading the story of Esther in the Old Testament.”

“That’s cool,” he said. He kept looking at my Bible, then asked “What kind of Bible is that?”

I stuck my thumb in place and closed the book to show him the front cover. “It’s a literary study Bible.” I could see he looked confused. “It’s a Bible that helps you study the Bible like a piece of literature—like a story, basically.”

“Ahh,” he said. “That’s really cool.”

He pulled out his phone, scrolled around for a moment, then turned back to me.

“Ma’am,” he said. “If you don’t mind me asking. Why would you study the Bible in that way?”

There it is. Yes. Why indeed?

Why would one bother to study the Bible as a work of literature?

Non-Christians, I think, have a much easier response to this question than those who claim the Christian faith; at least, those students of history, or anyone thoughtful at all about the origins of civilizations.

Why wouldn’t you? they’d say.

The Bible is a core text in the canon of western literature. Possibly more than any other book, it has influenced the shape of Western civilization. Every aspect of our society: from law, to work ethic, notions of family, human rights, culture and the arts; these and more have been crafted and colored in by a Juedeo-Christian worldview.

I’ll never forget when my husband (back then my boyfriend), in his freshman year at the University of Chicago (mid 1990’s), was assigned major sections of the Bible as required reading for his Western Civ. class. I was astounded. I’d never heard of reading the Bible at a secular institution for the purposes of understanding the foundations of our Western civilization. I’d never heard of reading the Bible at any institution for any reason outside of religious purposes.

Which leads to the obvious but oft overlooked point—especially by Christians today—that the Bible comes to us first as a literary form.

What do I mean by this?

I think the Introduction of the Literary Study Bible does an excellent job explaining this:

…the content of any piece of writing is commuicated through from. the concept of form needs to be construed very broadly here. It means anything having to do with how a writer has embodied his or her content, starting with the very words. Without literary form, no content can exist. We cannot extract the moral or theological meaning of a story without first assimiliating the plot, setting, and characters of the story, or the meaning of a poem without first pondering the poem’s images and figures of speech.

Every writer with something to say makes a conscious decision about how to best convey that thing. The writer chooses the form that will best embody—bring into full relief—what she or he wants to express.

So, as the editors say above, there no content if there is no form given it. In addition, there is a particular form best suited in the writer’s imagination that will best embody the content as the writer intends it to be expressed.

Think about the literary forms of the Bible. It’s primary genres (types of writing) are narrative and poetry. Within narrative we have: hero story, Gospel, epic, tragedy, comedy, parable, satire, drama, etc. Within poetry we find: lyric, lament, praise psalm, nature poem, epithalamion (wedding poem—I learned this from the study bible, lest you think I knew that word beforehand), and more.

Beyond narrative and poetry you will find: prophesy, visionary writing, apocalyptic, pastoral, oratory, epistle, travelogue…. The list is extensive.

What the Bible does NOT come to us as—contrary to how it is widely defined (and thus singularly treated) in much of modern American Christianity—is: “a handbook for life,” or “a rulebook for right living.” You’ll need to pick up a copy of the Boy Scout’s Handbook for that. Preferrably an early edition.

In saying the Bible isn’t a “handbook” I am not suggesting that it doesn’t have quite specific answers to the question: “How should we then live?” (to quote theologian, Francis Schaeffer). It does. As a professing Christian, I espouse them and effort to live according to them every single day—however flawed and failing. But, I do so because I read and understand the Bible first as an epic love story written for me.

“First.” This is a key word in the whole “read the Bible as literature” theme. Again from my Literary Bible’s Introduction:

…a certain priority needs to be given to literary form—not a priority of importance but a priority in the sense of what comes first. To approach the Bible as literature… is not like dessert—something pleasurable to add to more important aspects of the Bible. The literary approach is the first item on the agenda—the starting point for other approaches to the Bible. This has been a point of neglect among Bible readers and Bible scholars that this literary Bible aims to correct. (italics mine)

So, the short answer to the question, Why would you study the Bible in a literary way? is pretty simple: Because this is how it comes to us.

For those who believe the Bible is also the inspired Word of God, this understanding ought to give serious pause. The God who created monarch butterflies, blue herons, the giant sequoia, and the baobab tree—chose to narrate His existence, His thoughts, His purpose, His plan, and His love… all the things, by way of story and poem, parable and prayer.

If this is the way He chose to inspire the writers of the Scriptures to embody His Word, doesn’t it seem right and fitting that we give due diligence to exploring the form, and wondering what the form itself has to offer?

It’s interesting, the Bible is often called the “Living Word” by believers. It comes from the beginning words of John’s Gospel, “In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was God.” (John 1:1, a literary sentence if there ever was one). For believers, this phrase (outside of being another name for Christ) points to the reality that the Bible can speak into our present day with truth, goodness, beauty and wisdom as effectively as any other time in history from the time it existed.

The interesting part of this is that people who love literature will often suggest a same sort of “livingness” about their favorite stories, particularly classic works of literature. Such works have the power to speak something new and give fresh insight with every reading, at every stage of one’s life. The great 19th Century English educator, Charlotte Mason, called such works, “living books.”

It seems clear, that there is something about narrative and poetic forms that are “alive” able to breathe into us a kind of vivifying life. But only if we have eyes to see, ears to hear, and hearts open for understanding.

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this idea of reading and studying the Bible as literature. Agree? Disagree? Agree but have no clue where to begin??

If there’s an interest in this topic, and a curiosity for “how” to read and study the Bible as literature, I would be glad to offer a series of posts to help guide and encourage you in the process. Maybe we can even start a “literary Bible study” sub-group that studies books of the Bible in this literary way. That could be fun!

Thanks for reading everyone. I know your time is valuable, and I am honored that you would spend some of it with us here at the Reader & the Writer.

Much Love,

Shari

Loved the connection of CM’s quote to read “living books” and the Bible as the “living word”. We know CM was Christian and her approach to education was based on Biblical principles. Now I’m leaning into this new approach to reading the Bible and want to share with my kids too!

I love the idea of a literary Bible study.